This article is an independent version of the article featured in this issue of DOK Architecture Magazine. You can access the entire journal via this link:

When it opened in AD 80, tens of thousands flowed through 80 numbered gates, clay ticket shards in hand, each shard mapping a precise route to a precise seat. Inside was a machine. an elliptical arena wrapped by uninterrupted tiers so every eye met the sand and nowhere else.

Roman engineers doubled the semicircle of the Greek theater into a full ellipse to keep action centered and sightlines clean.

Steeply raked seating reduced bad angles. Even the cheapest rows could read a spear’s arc or a lion’s leap.

The geometry did narrative work. Fifty thousand pairs of eyes synchronized on one stage, a single body breathing in unison.

An oval of travertine and shadow, the Colosseum turned cruelty into choreography.

Beneath the timber floor lay the hypogeum, a two-level maze of corridors, capstans, elevators, and trapdoors.

Crews worked like a ship’s company, timing lifts so animals, trees, props, or fighters erupted “from nowhere.”

Reconstructed mechanisms show teams of eight hauling a single elevator.

Multiply that across dozens of shafts and you get a programmable theater centuries before the word existed.

In the earliest years they may even have flooded the arena for brief naval tableaux, but once the permanent hypogeum arrived, vertical spectacle won out over water.

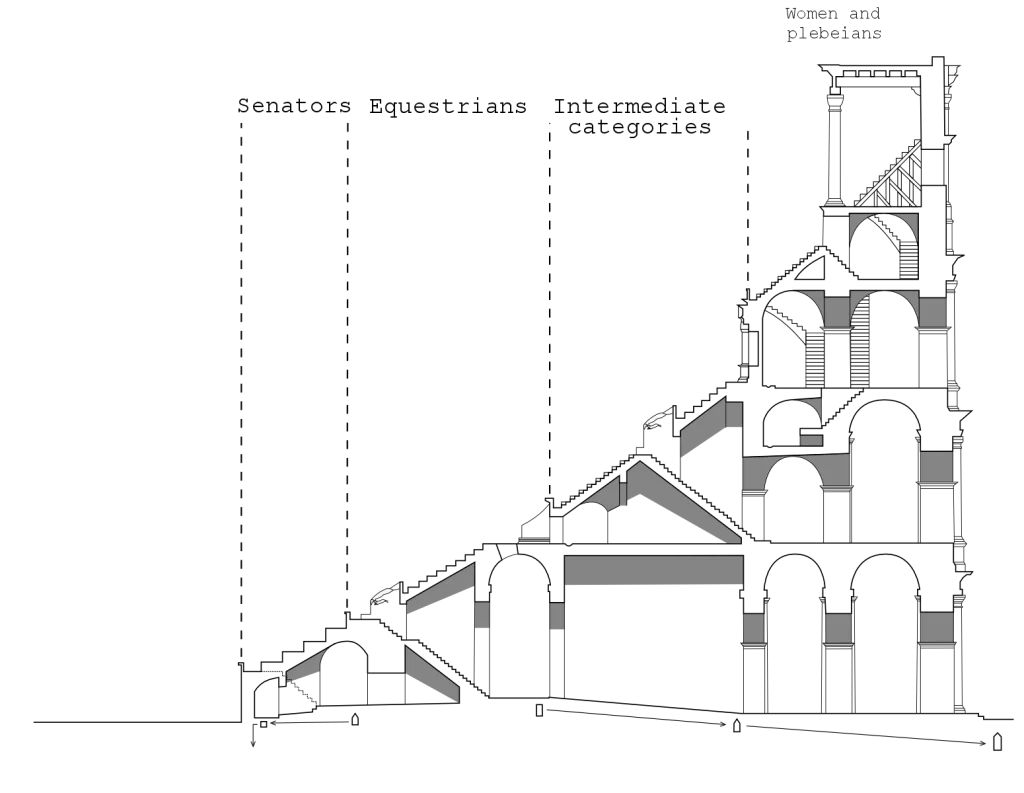

The seating arrangement encoded status as clearly as a legal text. Emperor and vestals on the short axes. Senators on the marble podium brushing the arena wall; equites above; citizens tiered by wealth. Women and the poor relegated to the upper wooden gallery. Comfort mapped power. Armrests and legroom below, cramped benches and heat above. Architecture didn’t just house society, it taught it, with each event rehearsing hierarchy.

Crowd management was unnervingly modern.

Numbered gates, painted markers, carved stair codes, stacked concourses, and those famous vomitoria could fill and empty sections in minutes. Circulation was control.

Classes entered separately, moved on separate paths, and left without mixing.

A spatial guarantee against chaos.

Rome used physics. The velarium, a vast retractable canopy worked by naval sailors, stretched like an inverted sail, casting migrating shade and pulling breezes through the arcade ring so hot air rose and cool air slipped in. Sand absorbed blood. Drains cleared the floor. Fountains and latrines tucked into the vaults kept crowds functional. The same systems that soothed the audience kept the program on schedule, converting horror into routine.

Why does it still grab us?

The DNA of the stadium hasn’t changed.

Central stage, raked bowl, clear pathways, quick exits. We recognize the template because we keep building it, from stadiums to ballparks.

Ruin holds more than engineering.

Layers of reuse, plunder, devotion, romance.

It has been a fortress, a quarry, a garden, a symbolic structure that becomes a memory, a memory that becomes a lesson.

The Colosseum is both breathtaking and disturbing. Its elegance served state violence with industrial efficiency. This dissonance is the point. Technical perfection can advance terrible ends. Choreography can numb the conscience. The amphitheater reminds us that architecture is never neutral.It encodes logistics, power, comfort, and values, sometimes in conflict.

Today, restoration work is keeping more than half of the perimeter standing. Projects are testing reversible floors to allow visitors to stand at arena level again. On nights when a death sentence is commuted somewhere in the world, the arches glow in a modern ritual that rewrites a theater of death as a lantern for life. The building continues to “perform,” but now as instruction rather than incitement.

Precision of form, clarity of movement, sense of environment, legible hierarchy – these are the transferable lessons. The caution is also transferable.

Don’t confuse brilliant staging with moral success.

The Romans mastered the user journey but they also normalized cruelty.

Two thousand years later, as we pass through turnstiles into climate-controlled bowls and find our color-coded seats, we’re still working with the same toolkit. The question is whether we’re arranging space for dignity or just for distraction.