Aging is becoming commonplace in cities, not an exception. United Nations projections indicate an unprecedented increase in the population aged 60 and over, which will reshape how homes, streets, and services function together. Healthcare institutions argue that places that support the bodies and minds of older adults are better for everyone, from children to caregivers. Therefore, designing for longevity is not a niche topic, but the new foundation of public life.

You should definitely read Bruce Broussard’s article on this subject:

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/designing-aging-world-leading-empathy-building-bruce-broussard-6vlge/

Understanding Demographic Change

As population structures shift toward older age groups, urbanization is progressing toward a world where approximately 70% of the global population will be urbanized by the middle of the century. This combination concentrates older residents in densely populated areas that require more care, accessibility, and resilience per square meter. Recent policy studies emphasize the social and economic importance of getting this right. If we design poorly, we could face numerous problems, from isolation and labor force loss to higher public expenditures. The demographic curve is no surprise, making failure to respond to it a design choice.

The Global Increase in the Aging Population

The proportion of elderly people is increasing in every region, and it is estimated that by the late 2070s, the number of people aged 65 and over will exceed the number of children. This change is not only related to longer life expectancy, but also to spending more years in cities built for younger bodies and different risks. Countries are experiencing this transition at different speeds, but the direction is the same. The task for architects is to clearly express this macro-level reality at the street level.

Longevity and Built Environment

Longer lives enable daily environments to function as health infrastructure, from light and air to thresholds and finding one’s way. Evidence links specific indoor factors such as lighting, thermal comfort, air quality, order, and barrier-free movement to the health of older adults. Global initiatives define this as “age-friendly” environments that enable people to continue doing the things they value throughout their changing abilities. When these elements are well-calibrated, the built world becomes a silent caregiver.

Urbanization and Its Effects on Infrastructure

As cities grow, the systems that provide water, energy, transportation, and maintenance services must serve people who move more slowly, see differently, and require more rest stops. Many rapidly growing urban areas still face problems of informal housing and inadequate public facilities, which makes aging safely a daily logistical challenge. Cities that plan for shorter trips, mixed-use developments, barrier-free networks, and nearby services reduce costs while enhancing quality of life. The return on investment is evident in reduced hospital admissions, increased participation, and the emergence of places people trust.

Why Should Architects Adapt Now?

Climate stress coincides with aging, and research predicts that exposure to dangerous temperatures for the elderly will nearly double by mid-century. This transforms shade, ventilation, cooling access, and green infrastructure from mere comfort features into life-saving elements. Cities have already begun creating prototypes of senior-friendly neighborhoods that combine adaptable housing, inclusive mobility, and social infrastructure to prevent isolation. The tools are available, timelines are public, and each new project either widens or closes the risk gap.

Universal Design Principles

Universal Design is a commitment to ensure that products, spaces, and services can be used by as many people as possible without requiring special adaptation. The UN Convention defines this as designing for everyone whenever possible, while allowing for the use of assistive devices when necessary. NCSU’s classic seven principles translate this ethic into practical qualities such as equality, clarity, tolerance for error, and minimal effort. In short, UD is not a niche extra feature, but a fundamental part of public life.

The True Meaning of Universal Design

Universal Design shifts the designer’s question from “who is typical?” to “which bodies, senses, and minds will use this?” The UN definition emphasizes broad usability rather than specific exceptions, which keeps inclusivity cost-effective on a large scale. NCSU principles provide a common language across disciplines so that buildings, products, and communication can target the same human goals. As a result, fewer barriers, fewer temporary solutions, and a better quality of daily life are achieved.

Essential Elements for Accessibility and Inclusion

In the built environment, ET manifests as equal access, simple and intuitive layout, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, and sufficient size and space for approach and use. Multisensory wayfinding, lighting that supports contrast and comfort, clear access and turning areas, and step-free continuity transform these concepts into a readable space. While codes such as ADA Standards define minimum technical and scope requirements, ISO 21542 and BS 8300 expand the summary in the direction of multi-sensory communication and inclusive circulation. Think of the codes as the foundation, and Universal Design as the target state that most people actually feel.

Examples of Universal Design Success

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park has embraced inclusivity from the proposal stage to the legacy stage, thanks to customer-side leadership, an independent accessibility panel, and binding Inclusive Design Standards. The result is a large urban area with accessible spaces, routes, and programs that treats inclusivity not as an afterthought but as a fundamental quality. The Park Design Guide keeps this standard alive as the area develops, ensuring that inclusive details are a factor in the evaluation of new projects.

Singapur’daki Kampung Admiralty, yaşlılar için konut, sağlık hizmetleri, gıda ve kamusal alanları engelsiz bir “dikey köy”de bir araya getirerek, UD’nin nasıl bir sosyal altyapı olabileceğini gösteriyor. Teraslı parklar, oturma alanları, gün ışığı ve basamaksız geçişler, yaşlılar için günlük hareketleri güvenli ve onurlu hale getirirken, diğer herkes için de fayda sağlıyor. Bağımsız değerlendirmeler, dolaşımdan dinlenme noktalarına kadar her alanda Evrensel Tasarım ilkelerinin uygulandığını belirtiyor.

Standards, Guidelines, and Emerging Norms

The toolkit is clear and growing stronger: ADA 2010 sets minimum standards in the United States, ISO 21542:2021 provides international requirements for access, circulation, and evacuation, and EN 17210 codifies the Design for All approach across Europe. The UK’s BS 8300 and New York City’s Inclusive Design Guidelines go beyond minimum requirements with multi-sensory guidance and urban applications. The direction of travel is moving from a situation where accessibility is the exception to one where universal design, which aligns design quality with human rights, is the default.

Accessible Architecture in Practice

Accessibility is not a specialized field; it is the operating system of the entire project. Codes specify minimum path widths, turning areas, entrances, and door clearances, but inclusive guidelines provide clarity on multi-sensory wayfinding, lighting, and public space continuity. Consider ADA, ISO 21542, BS 8300, and NYC’s Inclusive Design Guidelines as a unified toolset that transforms compliance into comfort. Design that works quietly for more people creates spaces people trust.

Entrances, Circulation, and Wayfinding Design

The entrance begins with step-free paths, open approach areas, and doors that open with minimal effort and provide sufficient maneuvering space; ADA requires a minimum clear width of 32 inches at doors, turning areas, and normal passageways when paths are narrow. Circulation should have gentle slopes, wide corners, and no clutter on accessible paths; it should have passage and turning areas suitable for actual devices and should not be based on drawings. Wayfinding works best when information is layered: first intuitive layout, then clear sightlines, consistent wayfinding cues, and legible signage prioritizing primary directions. Transitions from outside to inside utilize tactile cues, consistent curb language, and accessible pedestrian signals.

Material and Detail Options for Safety

Choose hard, sturdy, non-slip, and non-glare surfaces; combine this with even lighting to reduce falls and fatigue. On stairs, provide continuous handrails on both sides, good lighting on the top and bottom steps, and high-contrast step edges to ensure the edge is visible. Tactile warnings in hazardous areas and passageways should comply with local standards and use tonal contrasts rather than complex patterns that confuse depth perception. Small choices such as matte surfaces, contrasting-colored handrails, and clear thresholds reduce accidents and anxiety.

Multi-sensory and cognitive accessibility

Make the building understandable not only through sight but also through touch: combine visual contrast with tactile cues, clear acoustics, and a simple information hierarchy. For cognitive accessibility, keep layouts predictable, prevent dead ends, use recognizable symbols, and place the most important wayfinding information at the forefront. Dementia-friendly research emphasizes light quality, strong contrast at decision points, and continuity of wayfinding cues to support memory and orientation. NYC’s Inclusive Design Guidelines translate this into a multi-sensory application for interiors and streets.

Adapting Existing Structures in a Respectful Manner

Improvements made to existing buildings should eliminate barriers that can be easily addressed and, to the extent that finances and building permits allow, implement larger changes gradually, all while preserving the character of the building. Historical settings can be equipped with elegant ramps, elevators, and handrails that preserve heritage if instructions are clear and options are evaluated early on. The goal is not a back entrance, but equal access and equal use. National guidelines demonstrate how access can be integrated as good design rather than an afterthought.

Future Trends and Design Ethics

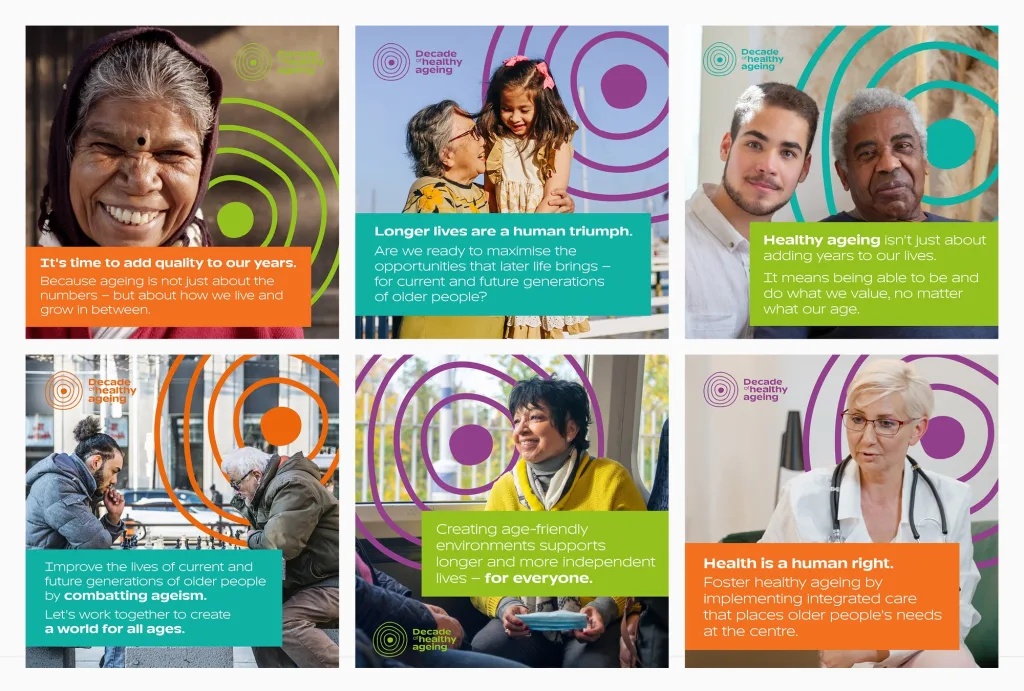

The next phase of age-friendly design lies at the intersection of demographics, climate, and digitalization. While the UN Decade of Healthy Aging reshapes approaches to functional ability and inclusivity, the latest population projections clearly show that older adults will shape the functioning of every region. At the same time, digital systems are impacting care, mobility, and social life, giving rise to new responsibilities regarding governance, transparency, and trust. The ethical horizon is a concept that is easy to articulate but difficult to implement: designing spaces and technologies that extend healthy life expectancy without restricting rights.

Technology and Smart Aging Environments

Sensors, telehealth, and building systems are becoming the silent infrastructure of independence, transforming homes and neighborhoods into responsive health support systems. The smart city guide promotes open, citizen-focused operating models so that these systems serve people rather than trapping them in vendors’ silos. Healthcare artificial intelligence can increase its benefits, but this is only possible if it is managed for security, accountability, and human oversight throughout its lifecycle. The architectural task is to pair environmental technology with explicit consent, data minimization, and graceful failure, so that autonomy is preserved when systems falter.

Equality, Dignity, and Intergenerational Design

Rights form the foundation: Accessibility to the built environment is not a matter of style preference, but a legal requirement and a principle of dignity, as stated in UN policy for older adults. Cities that blend age-friendly and child-friendly agendas create streets, housing, and parks that encourage participation at every stage of life. Intergenerational models demonstrate social benefits, from students living in senior housing to childcare integrated into elder care. Design for solidarity is visible in daily proximity, shared routines, and spaces that normalize care.

Architectural Responsibility in Social Aging

Heat, insulation, and fragmented services are design issues long before they become medical problems. Evidence shows that older adults face rapidly increasing heat risks. This makes access to shade, ventilation, and cool shelters part of a life safety strategy. Age-friendly frameworks and urban guidance translate this into programs, benchmarks, and steps toward public spaces that keep people connected and active. Architects should measure their work not only by compliance but also by harm reduction and increased sense of belonging.

Preparing Cities for 2050 and Beyond

By mid-century, more people will live longer in warmer, denser cities, meaning every masterplan must integrate aging and climate adaptation from day one. Cooling tools and nature-based strategies offer scalable, neighborhood-level measures that lower temperatures and improve health equity. Smart governance standards help harmonize data, services, and operations, while age-friendly indicators make progress understandable for the public. The goal is simple: a city where aging feels ordinary, supportive, and local.